Behind the Doors: The First Days at the Assessment Centre

Behind the Doors: The First Days at the Assessment Centre

Walking through locked doors, waiting rooms and paperwork, this is what a psychiatric assessment centre really looks like for a mum.

Content warning: This post talks about self-harm and suicidal thoughts. If you’re in immediate danger, call 999. In the UK, Samaritans are on 116 123.

Last week, Sydni was admitted to a psychiatric assessment centre. It’s not somewhere you ever imagine taking your child, and it’s not the kind of story I thought I’d be writing, but this is where we ended up.

Getting her there was brutal. She didn’t want to go. She said more than once that she’d rather die than walk through those doors. If she hadn’t gone in voluntarily, they would have sectioned her. That word alone made my stomach turn. In the end, after hours of persuasion, she agreed. It wasn’t relief or victory, just the least worst option.

The process

You buzz to get in and sit in a waiting room. It’s usually empty, but the surrounding rooms often aren’t; they’re full of people brought in by the police. Then you wait for the team to come and collect your child. They take them through another locked door and check all their belongings.

We also had to fight again for her to have an ensuite. With her health needs and the trauma she carries, sharing isn’t an option. But it always feels like you’re battling for the basics, which is exhausting when you’re already broken.

The staff

The team of which includes a mix: a consultant psychiatrist, mental health nurses, healthcare assistants, and activity coordinators. Oddly, no psychologist, God Knows Why Not!!! The staff are decent, human, stretched thin, and often tired. They want to help, but you have to keep speaking up or your child’s needs get lost in the noise.

What you actually have to bring

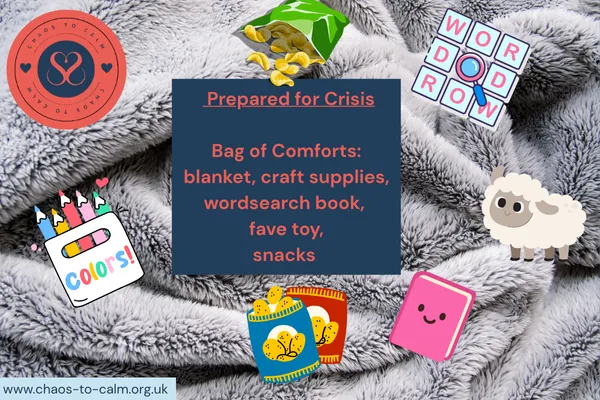

They don’t provide much, so you pack like you’re kitting out a little survival kit. We take blankets, soft things, and especially activities. Sydni loves crafts, diamond art, colouring, wordsearches and when she’s in crisis, those things are sometimes the only way she can stay calm. She doesn’t just need them, she needs them. Without something to do, the nights stretch on and the distress ramps up.

Nights

Nights are the worst. That’s when she gets the most distressed. Her self-harm is always bad, but when she uses her own hands it’s horrific. Scratching until the skin comes off. You feel helpless, sitting at home, knowing the ward staff are doing their best but that the urge doesn’t just go away because she’s behind a locked door.

Small things that matter

None of this is easy. But a few things made the first days just about manageable:

Showing up, even when I couldn’t fix it.

Arguing for her needs, like the ensuite.

Making sure she had the right activities with her.

Finding small “normal” things for myself on the outside, a shower, a dog walk, one trusted friend to text.

The wins were tiny: she stayed in the building, she accepted a snack, she sat with other inpatients and coloured. They sound like nothing, but in that setting they mean everything.

This is the reality, not the neat version, but the one that parents like me live.

It’s raw, it’s relentless, and it’s a constant balance between holding on and falling apart.

Your calm in the chaos,

Sami xx